Table of Contents

- Cancer Clinical Trials: The Navigator’s Role in Ensuring Inclusivity

- The Devil You Don’t Know: Cancer of Unknown Primary Origin

- Understanding Value-Based Care and Alternative Payment Models

- Policy and Advocacy Committee Reviews Work, Discusses COVID-19, Medicaid Expansion

Cancer Clinical Trials: The Navigator’s Role in Ensuring Inclusivity

Touching every area of society, issues of race are complex and deeply embedded. Cancer clinical trials are no exception. An examination of the demographic makeup of cancer clinical trial participants reveals most are white, well-educated, and have private health insurance. This seems counterintuitive, as cancer research provides medically underserved, underinsured, or uninsured patients access to cutting-edge treatments that they would not otherwise be able to obtain.

“We really need to reach out and include others,” asserted Linda Burhansstipanov, MSPH, DrPH, who identified herself as a member of the Cherokee Nation. “If we’re not included, then we don’t have the chance to influence the protocols used for the clinical trials.”

She went on to explain that Native Americans are an example of an underrepresented group in clinical trials, and one that has received inferior care compared with other races.

“Their life expectancies are actually quite a bit lower,” Daniel Petereit, MD, FASTRO, said of residents of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

Indeed, their life expectancy is the lowest in the United States, at 48 years for males and 52 years for females. With high rates of high-risk health behaviors and comorbidities resulting from social stressors, as well as low screening rates because of the lack of resources, trust, access, and health literacy, it is no wonder Native Americans are more likely to have advanced-stage cancer at diagnosis and are less likely to receive cancer-directed therapies after diagnosis compared with their non-Hispanic, white counterparts.

One need only look at the benefits of clinical trials to understand the importance of making them more inclusive, Dr Burhansstipanov said. Treatments validated in clinical trials have improved patient outcomes. In addition, new approaches to treating once-untreatable cancers have come from clinical trials. In some studies, patients may receive more careful and regular medical attention than received with standard treatment. It has also been shown that healthcare providers involved with clinical trials typically offer higher-quality care and access to the most recent validated treatments.

Multiple barriers stand in the way of underrepresented patients participating in clinical trials. Poverty and its accompanying pitfalls can affect compliance with trial protocols. Also, a trial could be considered lower in priority than other life issues that may be more pressing.

Cultural perspectives also play a role. Some minority groups feel disenfranchised and have feelings of distrust toward the medical establishment. Accordingly, many see clinical trials as only beneficial to the researchers, not providing enhanced access for their communities. These and other beliefs may deter underrepresented individuals from taking part.

“We do have a lack of sense of ownership of the research,” Dr Burhansstipanov said. “We hear comments: ‘It’s only for white people,’ or ‘It’s only for rich people.’”

Providers contribute to the issue in their own ways. Implicit or explicit biases may prevent them from referring underrepresented populations to clinical trials. For example, even African American doctors are less likely to refer African American patients to clinical trials. Also contributing is the perception that people from minority groups are less likely to comply with trial protocols. Sometimes, providers are simply too busy to explain clinical trial opportunities to patients, or are unaware of available resources, including transportation or lodging, that could help improve retention.

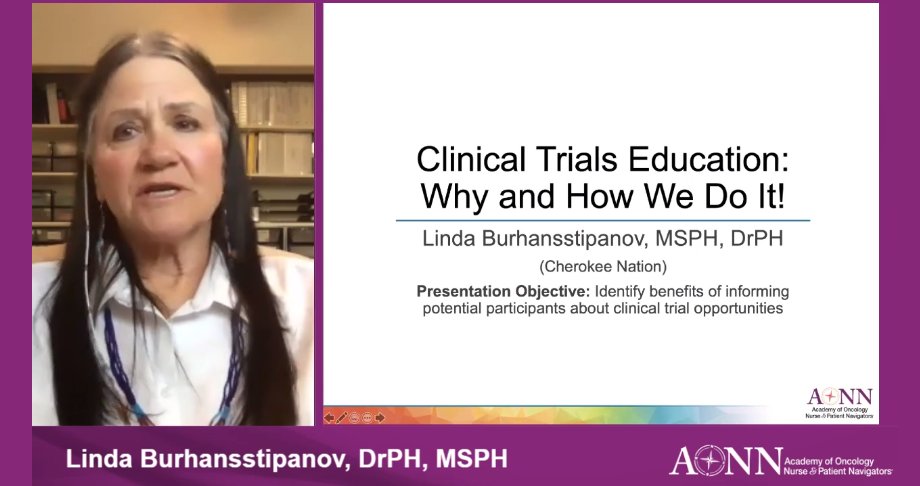

The oncology navigator’s dynamic role should include educating patients about clinical trial enrollment opportunities, according to Linda Krebs, PhD, RN, AOCN, FAAN.

“We try to allay some of the fears people might have,” said Dr Krebs, adding that patients often express that they don’t want to serve as “guinea pigs” and education can help. “You may want to help create community programs.”

Along with Dr Burhansstipanov and others, Dr Krebs did just that, co-founding the Colorado Blueprint, a program to increase clinical trial enrollment among underrepresented populations; the 7Cs, the Colorado Culturally Competent Clinical Cancer Care Curriculum; and Clinical Trials Education for Native Americans.

Dr Petereit is also leading the charge toward making clinical trials more inclusive. As principal investigator of Walking Forward, a community-based research program funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to address high cancer mortality rates among Native Americans in Western South Dakota, he is well-versed in the need for building a foundation of trust in a community to foster greater participation in clinical trials.

“From the NCI’s perspective, they want 2 things: They want patients in clinical trials and they want manuscripts. That’s the icing on the cake for us,” he said, adding, “I really think the core of what we’ve done in our patient navigation program is establish trust within the communities. We often say Walking Forward is a research program with a service component.”

To find cancer clinical trials, visit the NCI website (cancer.gov) or call 800-4CANCER.

The Devil You Don’t Know: Cancer of Unknown Primary Origin

A 55-year-old woman with liver disease received a liver transplant. In the removed liver, doctors found a grade 1 well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor. Because primary neuroendocrine tumors in the liver are largely unheard of, pathologists delved deeper to deduce the originating site of the patient’s malignancy. The histology of the tumor pointed to an origin in the small bowel, or more specifically, the terminal ileum. Doctors took a closer look at the patient’s imaging and confirmed the presence of a lesion in that area. Soon after, they removed from the patient’s terminal ileum the small primary tumor that had metastasized to her liver.

“If the primary [tumor] had been kept in there, it would have continued to shed malignant cells that would have continued to spread through the body and particularly go into her new liver,” said Emma Furth, MD, Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who identified the primary site in this patient. “By our ability to not only diagnose that the tumor is a neuroendocrine tumor but even to further refine what the primary site was, we were able then to help in terms of subsequent treatment that will hopefully extend the life of this particular patient.”

Although pathologists are typically able to determine a primary malignancy, in rare cases, tumors cannot be traced to their site of origin, Dr Furth explained during a session on the topic. Making such a determination is vital, as the originating site of a cancer determines its prognosis and treatment.

“We do still have cancers of unknown primary, but they represent a truly small percentage of malignancies with which we deal,” she said. “Even in those situations where we can’t say with absolute certainty where it started, we can tell you pretty much in a probabilistic manner what we think the odds are of the primary site.”

A first step in understanding cancers of unknown primary is comprehending pathology. Composed of a multitude of professionals with a variety of skill sets, pathology departments are staffed by much more than pathologists. In addition, Dr Furth pointed out, many people do not realize that pathologists are physicians, and although they work with specimens taken from patients, they indeed are part of the multidisciplinary team providing patient care.

“Most people think of pathology as…a big black box, and they think we put the specimen into this black box and out spits an answer,” she said.

Pathology involves histology, or the examination of specimens under a microscope, but includes much more. Ancillary predictive and prognostic marker testing help to determine the best treatments for a patient.

For example, not all adenocarcinomas are treated the same. The origin of the carcinoma determines which chemotherapeutic options will be employed in fighting the cancer. Fortunately, some underlying mechanisms can help to tease out a diagnosis.

In neoplastic progression, genetic or epigenetic changes drive benign cells to develop the malignant phenotype. Although such cells change in appearance, they retain some characteristics from when they were benign.

“We try then to work backwards, given a malignant cell, what do we think it most looks like in terms of its benign counterpart,” Dr Furth said, adding that the process is not as straightforward as it sounds.

As a cell undergoes genetic mutations or changes on the road to becoming malignant, it may no longer resemble the benign cell it once was, complicating matters further. Also, these changes in the cell affect its behavior. Fortunately, pathologists have the ability to establish what changes have occurred in the cell’s progression toward malignancy, thereby providing insight into the pathway of the malignancy. Sometimes, however, molecular changes in the nucleus of a cell can make it so dedifferentiated that it is unrecognizable.

“That might be a situation where we truly have a carcinoma or malignancy of unknown primary,” Dr Furth said, adding that in such cases, pathologists are able to examine the proteins or antigens expressed on a cell through immunohistochemistry to provide insight into its pathway.

Pathologists do not work in a vacuum, however. Tumor boards and multidisciplinary team meetings help them to make their determinations.

“Not any one piece of data may yield the diagnosis,” she said. “One has to integrate and put all the pieces of the information together.”

Because of this, communication is crucial, according to Dr Furth, who said she regularly communicates with nurse navigators and other members of the clinical team, along with patients and families, with the latter being relatively unique among pathologists.

“I am a true believer in that the more we know, the better we are and knowledge is indeed power,” she said, adding, “Communication and teamwork are absolutely paramount. We can’t render great patient care without that.”

When pathologists provide a diagnosis by composing a report, its contents may not be easily understood by the clinician reading it.

“If in reading the report, one doesn’t fully understand what is being said, calling the pathologist of record would be the next step,” Dr Furth advised. “Don’t think the report is the end of the road at all.”

Despite the many tools available to pathologists, some malignancies remain a mystery in terms of their origin.

“In this day and age, it’s really actually rare to have a malignancy of unknown primary,” Dr Furth said. “It does happen for sure, and in those situations we do our best. We can say where it’s not and we can say what it might be. And sometimes, that is the best we can do.”

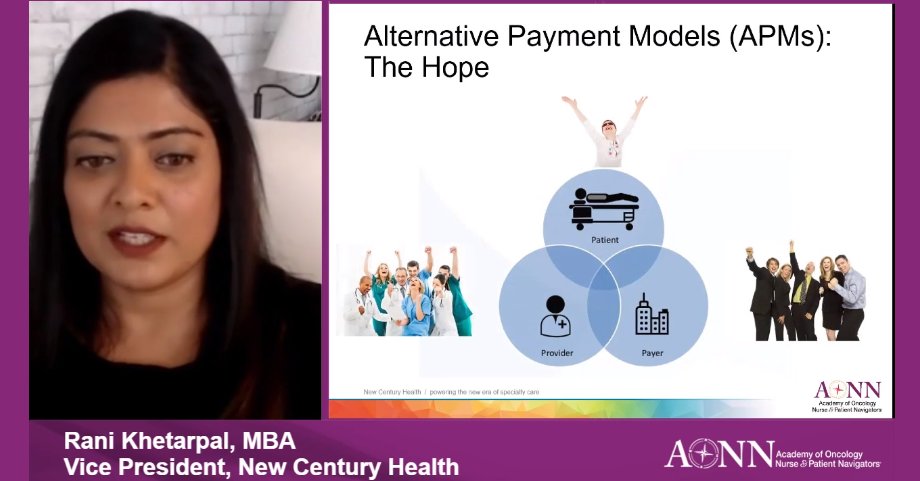

Understanding Value-Based Care and Alternative Payment Models

Aimed at providing higher-quality care without increased cost, value-based care and alternative payment models (APMs) are well-intentioned undertakings but can be nonetheless vexing for those involved. Providing a clearer picture of these concepts and what they entail, Rani Khetarpal, MBA, offered an overview for attendees.

“The good news is that we’ve learned a lot in the last decade or so,” she said.

The Oncology Care Model: A Closer Look

Originally a 5-year pilot introduced by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2016 to test episode-based payment incentives and move away from the fee-for-service (FFS) model, the Oncology Care Model (OCM) sought to incentivize value-based care by enhancing communication between providers and patients; recognizing depression and distress in patients with cancer; addressing financial toxicity; and improving care coordination, symptom management, and palliative and end-of-life care. Extended through July 30, 2022, because of COVID-19, the OCM is based on 6-month episodes of care, and includes 95% of chemotherapy patients, 138 practices, and 10 commercial payers. Episodes include the total cost of care, encompassing all types of service and diagnoses.

“It’s being used as a foundation to build other APM models that look at total cost of care,” Ms Khetarpal explained, adding, “It sounds simple in theory, but it’s really not.”

Initially offering upside-only risk for participants, the OCM also provides the option for 2-sided risk.

Practices can still bill FFS payments under the OCM, but the program also includes Monthly Enhanced Oncology Services (MEOS) payments, along with the potential for performance-based payments (PBPs) if practices achieve savings and a quality score greater than 30%, Ms Khetarpal said.

Savings are determined using a benchmark episode price, which is set using a complex formula based on multiple factors. Determining quality score involves the use of 12 quality metrics that fall within 4 domains, including communication and care coordination; person- and caregiver-centered experience and outcomes; clinical quality of care; and patient safety.

Oncology Care Model Risk Choices

The advent of the OCM came with an upside-only risk model that rewarded participating practices with a PBP for the provision of quality care within the pricing target established by CMS. Practices were not penalized for exceeding this target, however. Representing the greatest risk for providers, 2-sided risk models hold practices accountable for costs above the established target, although practices qualify for larger payments under this model and avoid Merit-based Incentive Payment System requirements, as well. Practices that had not achieved savings under the upside-only model were required to enter into 2-sided risk or drop out of the OCM in January 2020.

Challenges

The OCM comes with its share of challenges for participants.

“Identifying OCM beneficiaries and episodes has been a challenge,” Ms Khetarpal said, adding that the requirement of presenting patients with estimated out-of-pocket expenses represents another hurdle. “As we know, that’s a very difficult thing to do, to predict what’s going to happen.”

Reporting and data registry requirements represent a wieldy undertaking, and quality measures can be difficult to attain. The data reporting timeline represents yet another obstacle.

COVID-19

Resulting in a 1-year extension of the OCM, COVID-19 also brought about the exclusion of total clinical episodes from reconciliation if they included a coronavirus diagnosis. The pandemic has also impacted risk arrangements, with the option to forego upside and 2-sided risk, and MEOS payments remaining applicable. The PBP, however, does not remain applicable, including potential paybacks to CMS.

Ms Khetarpal said volume is going to be a major factor in the impact of COVID-19 on the OCM.

“I think it’s kind of wait and see,” she said. “But I think we’re going to learn a lot as we go forward.”

Successful Alternative Payment Models

The performance drivers most impactful on the success of APMs fall under 3 categories—drugs, emergency and inpatient care, and end-of-life care. Regarding drugs, using evidence-based pathways, point-of-care decision support, and accountability and adherence metrics results in less expensive drug regimens without compromised quality, along with targeted interventions for patients. In the realm of care, real-time risk stratification, formalization of the nurse triage process, and managing “frequent fliers” in the emergency department pay off with consistent triage and targeting of high-risk individuals. At the end-of-life stage, earlier palliative and hospice care, patient education, and provider engagement offer dividends in the form of improved end-of-life transitions and advanced care planning, Ms Khetarpal explained.

A breakdown of costs reveals Medicare Part B and D drugs as the largest category of spend, comprising approximately 55% of overall expenditures. Emergency and inpatient care represent 15% to 20%, with other costs completing the picture.

Successfully transforming one’s practice into a value-based care model is a multistep process, involving data gathering and analysis, care transformation, financial adjustments, and performance analysis.

“Every cancer center is going to have a different model that aligns with them,” Ms Khetarpal said.

The Oncology Care First Model

Under development by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, the Oncology Care First (OCF) Model is a sort of OCM 2.0, building on the former program. In lieu of FFS and MEOS, it would introduce a monthly population payment (MPP), along with dividing 2-sided risk into categories of more or less aggressive. All current quality measures and practice transformation initiatives would be maintained, with the potential addition of electronic patient-reported outcomes, for which practices would be allowed a ramp-up period to implement. Low-risk prostate, bladder, and breast cancers would be excluded. In addition, the pooling of providers will continue to be allowed under the model. Hospital outpatient departments will be able to participate if they partner with a physician group practice and more than 25% of chemotherapy is administered in the hospital outpatient department. The hospital outpatient department would also receive an MPP.

“There are a couple of very different factors between OCM and OCF,” Ms Khetarpal said. “The devil is in the details.”

Policy and Advocacy Committee Reviews Work, Discusses COVID-19, Medicaid Expansion

With a mission of advocating to protect and promote oncology navigation, the AONN+ Policy and Advocacy Committee is diligent in supporting that objective. Along with providing an overview of the committee’s accomplishments and a primer on advocacy, committee members delved into the impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer, as well as Medicaid expansion.

Kerri Medeiros, BSN, RN, OCN, ONN-CG(T), explained the fundamentals of advocacy, saying it can be conducted by anyone by:

- Contacting elected officials

- Signing coalition letters

- Voting and helping others to do so

- Writing newspaper editorials

- Attending town hall meetings.

“Elected officials are not experts in cancer care, but you are,” Ms Medeiros said. “Find out what you’re passionate about in cancer care and bring that out to your elected officials and to your community.”

Occurring at all levels of government, advocacy can take place around federal issues, such as Medicare, the Affordable Care Act, and the Healthcare Marketplace; it can also encompass state issues, including commercial insurance and state insurance marketplaces.

“No amount of advocacy is too small,” Ms Medeiros added.

With guiding principles of access, equity, affordability, patient-centered care, and patient assistance, the committee’s recent undertakings have included presentations, as well as helping to shape comments for a letter regarding the Oncology Care Model 2.0 and signing letters supporting the committee’s core tenets, with many focused on COVID-19.

COVID-19 and Cancer

Having immeasurable impact worldwide, COVID-19 brought with it the threat of greater mortality for patients with cancer. The directive by the American College of Surgeons and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for hospitals to cancel elective surgeries during the first months of the pandemic caused less aggressive cancer surgeries and other treatments to be delayed, according to Michele M. Hubert-Fiscus, MSN, RN, CCM. In addition, pandemic-related delays in care resulted in reductions in early cancer detection and restricted the ability to screen persons of average risk for colorectal and other cancer types. Colorectal cancer testing is of particular concern, with screenings already seeing a downturn and the pandemic further reducing screening by 80%, she said.

Along with facing an increased risk for contracting COVID-19 because of immunosuppressive treatment effects, patients with cancer have dealt with the conundrum of choosing whether to go to medical appointments and take a chance with getting the virus. Additional stressors, such as children being home-schooled, loss of employment and health insurance, transportation concerns, isolation, and possible lack of assistance because of reduced nonprofit revenues, only exacerbate the situation. The resulting psychosocial distress adds to the burden.

These issues became personal for Ms Hubert-Fiscus when her uncle was battling cancer, she said.

“For someone who was elderly and was really not sure what was going on, it was crucial for someone to be with him,” she said, adding, “So many people would not have had access to care if not for telehealth.”

Advocating for these patients includes working to ensure the elimination of copays for COVID-19 testing, reimbursement for telehealth, helping patients access additional financial assistance for those impacted by cancer and COVID-19, and having COVID-19 vaccination covered as a preventive service, among other efforts, Ms Hubert-Fiscus said.

Helpful for guiding patients with cancer through the pandemic is the new AONN+ COVID-19 Navigator Toolkit. Other ways to be an advocate for patients are to:

- Encourage a healthy lifestyle

- Educate on prevention and screening recommendations

- Empower patients and promote informed decision-making

- Identify and address barriers to care

- Transition them into survivorship programs when appropriate.

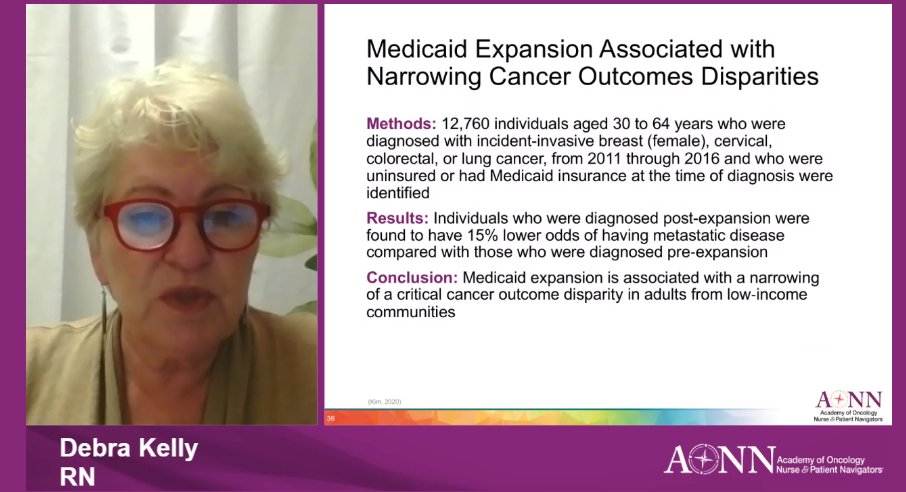

Medicaid Expansion Update

Part of the provisions of the Affordable Care Act, Medicaid expansion has thus far been adopted in 40 states, including Washington, DC, according to Debra Kelly, RN, BSN, OCN, ONN-CG. A boon for patients with cancer, Medicaid expansion is associated with fewer disparities in cancer outcomes, reducing the number of patients presenting with metastatic disease and increasing the receipt of treatment, resulting in longer median survival.

Looking beyond cancer, Ms Kelly cited studies showing Medicaid expansion has saved more than 19,000 lives over a 4-year span through regular checkups, early diagnoses, more prescription fills, and surgeries aligned with clinical guidelines. In addition, states with expanded Medicaid are better equipped to contend with COVID-19 and the accompanying recession, she said, adding that more than 650,000 uninsured essential workers could gain Medicaid coverage if states that have yet to do so adopted Medicaid expansion.

“They just tell me it’s not the political climate,” Ms Kelly said of holdout states. “The trick is just getting it on a referendum. Most people want it.”